A - B - C - D - E - F - G - H - I - J - K - L - M - N - O - P - Q - R - S - T - U - V - W - X - Y - Z

X

Xanthines

Pronunciation: ZAN-theenz

Definition: Xanthines are a group of alkaloids that act as mild stimulants and bronchodilators. In the context of nootropics, the most significant are the Methylxanthines, which include Caffeine, Theobromine (found in cacao), and Theophylline. Their primary mechanism of action is the competitive antagonism of Adenosine receptors, which prevents the inhibitory effects of adenosine on the central nervous system.

The Nootropic Research Interface

- Adenosine Blockade: Xanthines "occupy" the adenosine receptor without activating it. This prevents the "sleep pressure" signal from reaching the neuron, maintaining high levels of alertness and dopamine signaling.

- Phosphodiesterase (PDE) Inhibition: At higher concentrations, xanthines inhibit PDE enzymes, leading to an increase in intracellular cAMP. This secondary mechanism supports signal transduction and memory formation, making xanthines a powerful "potentiator" in many nootropic stacks.

Xanthone

Pronunciation: ZAN-thone

Definition: Xanthones are a unique class of polyphenolic compounds with a distinct symmetrical tricyclic structure. They are primarily found in the Mangosteen fruit and certain medicinal herbs. In nootropic research, they are prized for their high "oxygen radical absorbance capacity" and their ability to modulate neuroinflammation.

The Nootropic Research Interface

- Neuroprotection: Xanthones are studied for their ability to cross the blood-brain barrier and neutralize Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) within the brain, protecting the delicate lipid membranes of neurons from oxidative damage.

- MAO-Inhibition: Some specific xanthones have shown the ability to act as weak Monoamine Oxidase Inhibitors (MAOIs) in in vitro studies, suggesting a potential role in mood regulation and dopamine preservation.

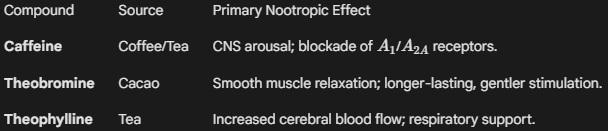

Xanthine Comparison in Research

Research Note:When formulating a stack using Xenohormetic agents, researchers must account for the "Stress State" of the botanical source. A plant grown in a perfectly controlled, stress-free greenhouse may actually have a lower concentration of these beneficial nootropic compounds than one grown in the wild.

Xenohormesis

Pronunciation: ZEE-noh-hor-MEE-sis

Definition: Xenohormesis is the biological principle that heterotrophic organisms (such as humans) have evolved the ability to sense and respond to chemical "stress signals" produced by plants. When plants are under environmental stress (UV radiation, drought, or nutrient depletion), they produce secondary metabolites—such as polyphenols—to protect themselves. When humans ingest these compounds, they trigger a "pre-emptive" survival response in our own cells, upregulating protective enzymes and longevity pathways even in the absence of direct stress.

The Nootropic Research Interface

Xenohormesis explains why many botanical nootropics are effective despite not being "nutrients" in the traditional sense.

- The Stress Mimicry: Many adaptogens (like Rhodiola rosea or Ashwagandha) are "xenohormetic." They contain compounds that mildly challenge our cellular systems, causing the brain to upregulate Heat Shock Proteins and antioxidant defenses, ultimately making the brain more resilient to future cognitive stressors.

- Sirtuin Activation: A primary pathway of xenohormesis is the activation of Sirtuins (specifically SIRT1). Compounds like Resveratrol (found in grapes) are studied for their ability to mimic the effects of caloric restriction, improving mitochondrial health and neuronal survival through this evolutionary mechanism.

- Hormetic Window: In research, xenohormesis follows a U-shaped dose-response curve. Small amounts of these "plant stress" signals are beneficial, while excessive amounts can become toxic. Determining the "Hormetic Zone" is the primary goal of dosing studies for botanical extracts.